Can an AI make up a language?

The question in the header is recurring in all AI circles. Those who work on NLP (Natural Language Processing) strive to develop systems capable of processing language produced by human beings and take according actions. GPT-3 is an example of this, the goal of this model is just to predict (although very accurately) the most likely word following a text sequence (Brown et al.). However, due to its training process, one cannot defend that the model has a deep comprehension of the words it is producing nor that it has an objective in mind by expressing them. I believe the leap we as human beings have ahead to cover this last hole is still huge and it will not come in the following years. After all, we still do not understand how human mind works. So the answer to the question in the header will be “it depends”. It depends on what we are referring to when we say “language”.

It is therefore relevant to know what we mean by “language” when we talk about it in this post. We will be referring to a common language shared by several systems through which they understand each other and transmit ideas. However, these ideas will come predefined by an agent external to the AI. A basic example could be to transmit a random number from 0 to 9 from system A to B in a common language, that B would process it, calculate its double, return it to A and A would receive the correct answer (the double of the first number). In this post we’ll try to lay the foundation for a project that meets all those requirements and one more condition: that the language shared by both systems is similar to that of the Star Wars R2-D2 Droid.

It takes two to tango

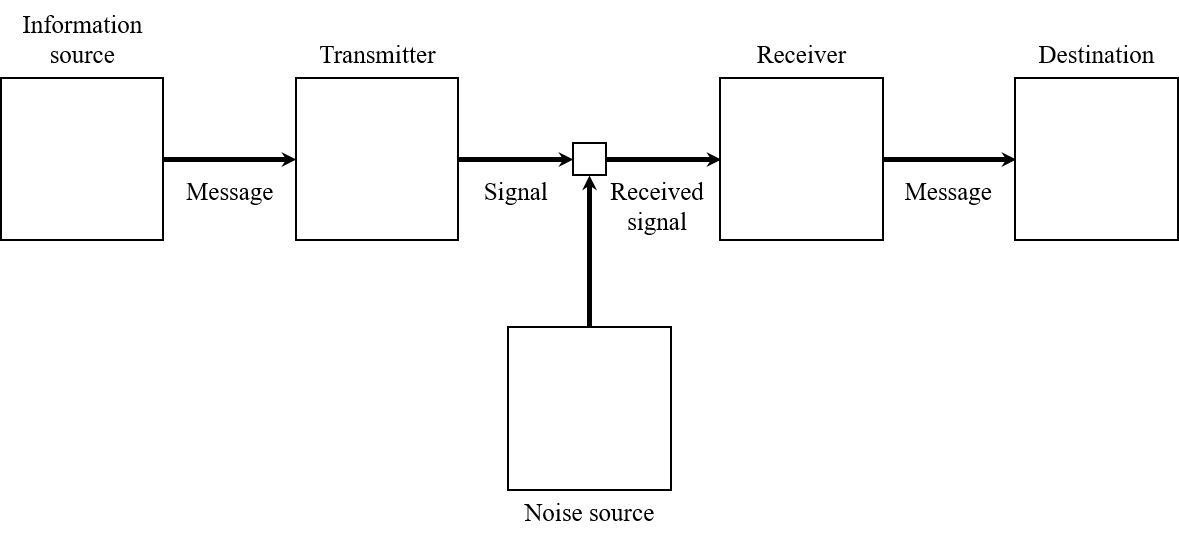

Indeed, for communication to exist there must be at least two systems: a transmitter of information and a receiver. Following the Communication Theory of Claude E. Shannon (Shannon), it is also necessary a source of information, a channel, a message, a destination and a noise source. While the precise definition of these components is left to the reader’s discretion, it is of paramount importance for this project to distinguish between information source and transmitter, and destination and receiver: when we talk about transmitter we refer to the technical system in charge of encoding the information source to a set of signals suitable for the channel (and vice versa for the receiver, which decodes it so that the receiver can use the information). Applied to verbal communication between two people A and B, the source of information will be A’s idea, whose brain will be in charge of coding it in the form of words - message - that will be sent through the air - channel - until it reaches B. B’s brain will decode the words and generate an idea, which in the best case will be the same as the idea of A’s brain.

Figure 1: Shannon’s Information Theory diagram. Adapted from (Shannon).

Figure 1: Shannon’s Information Theory diagram. Adapted from (Shannon).

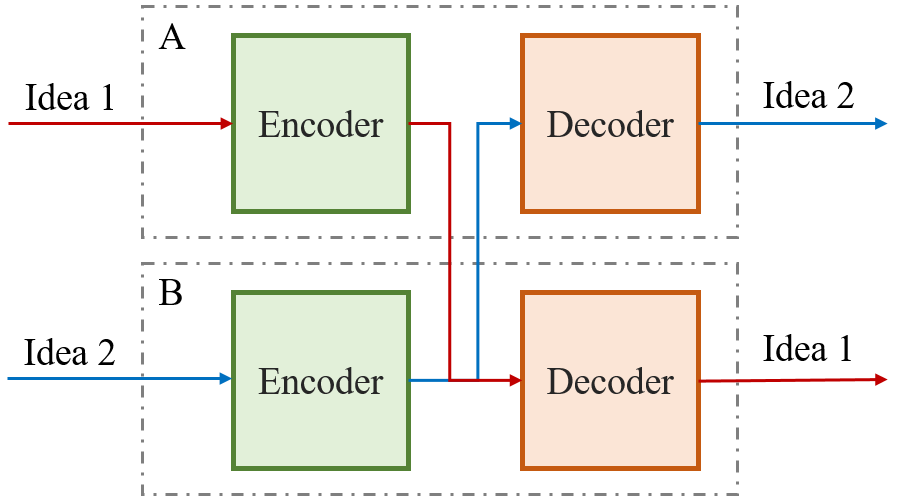

Let us now transform this theory into the field of AI. As we know, neural networks are tremendously effective in generating representations from data, so we could face two of them (subjects A and B) and make them share messages. A would encode the message and B would… decode it? And what would happen if B wanted to transmit an idea to A? To find the solution to this question we can look at the most efficient system we know when it comes to producing and processing language: the brain. This organ takes care of both functions simultaneously (or can’t you listen to music and talk at the same time?), and that is because the information flow passes through separate areas1. These two zones are Wernicke’s area and Broca’s area, which are in charge of understanding and producing language respectively (Neil). Following this example, it seems logical to make our subjects be formed by two different and disconnected networks. One of these networks, the encoder will be in charge of producing the language while the decoder will try to understand it. In case A wants to transmit an idea to B, A’s encoder will be responsible for transforming this idea into a common language and B’s decoder will interpret it.

Figure 2: Structure of a system with two subjects.

Figure 2: Structure of a system with two subjects.

Talking as clear as R2-D2

I will first describe R2-D2’s way of communicating for those who do not know it. It is a series of beeps, whistles and other sounds agglutinated to form something that resembles phrases (Bray et al.). On YouTube there are several videos showing these sounds. We will try to make the neural networks imitate this language when speaking, forcing the representation of the idea by the encoder to also be a series of beeps. However, forcing this type of representation is not trivial for two reasons: first, language must be created spontaneously through conversation between the networks, there must be no human interaction in this process. Secondly, we must define what we mean by “representation” in this context since language is very varied. We will address the second question first, which will lead us inexorably to the solution of the first._

A sound can be represented in three different ways depending on what we want to know about it:

- The temporal representation shows the intensity of the sound as a function of time.

- Representation in frequencies: explained very briefly, all sound, because it is a wave as a function of time, can be broken down into more basic waves with different frequencies. The method by which we go from a wave in the time domain to a wave in the frequency domain is called Fourier transform. The representation in frequencies contains information on how important (amplitude) each frequency is in giving rise to the underlying sound.

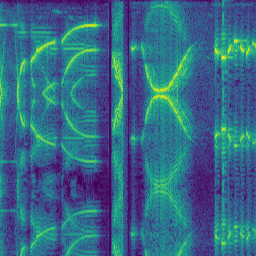

- Representation in the form of a spectrogram: the two previous representations have two dimensions, i.e. amplitude as a function of time or amplitude of each frequency. However, we can join both to produce a three-dimensional representation: time, amplitude and frequency. A spectrogram shows the evolution of frequency and intensity in time. Typically, intensity is defined by color, while time takes the abscissa axis and frequency the ordinate axis. Unlike the previous cases, a spectrogram can be saved as an image since the relevant information is coded both in the color of the pixels and in their position. The following figure shows the spectrogram of a voice fragment of R2-D22.

Figure 3: Spectrogram of a sound produced by R2-D2. It has been calculated by taking the Fourier transform of all the audio of the video in https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2-BKjnAgNgY and dividing the result in 256 pixels images.

Figure 3: Spectrogram of a sound produced by R2-D2. It has been calculated by taking the Fourier transform of all the audio of the video in https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2-BKjnAgNgY and dividing the result in 256 pixels images.

It has been shown that neural networks operate well with tabulated data and especially well with images (Krizhevsky et al.)(He et al.), so it seems logical to use the spectrogram for this task. In general, convolutional neural networks are used to work with images because they are capable of capture relations in their pixels, usually by identifying borders in different directions or other coarser features like textures. Explaining in detail how this type of networks work would be useful for another article, so it is left to the interested reader to become familiar with this type of architectures, since there are many resources available ((Stanford), for example). I will only say here that with a network of convolutional layers we can obtain a multi-dimensional representation of the input data (an image). That is, we can get the translation of any number in an image, and this translation can be learned for a concrete task.

A spoonful of architecture

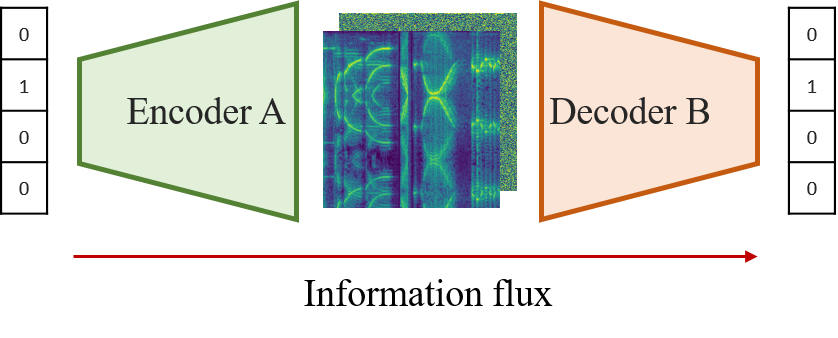

Once all the technical aspects of the problem have been addressed, we will focus on defining the system architecture and the training process. Determining network architecture is usually more of an art than a science, so I will not go into detail. First, we will code the idea (the number) in a One-Hot way, which means that to transmit a digit from \( N \) possible ones we will use a vector of \( N \) components with zero in all of them and one in the relevant component. For example, the vector for the number 1 in the interval \( [0, 4] \) will be \([0, 1, 0, 0, 0]\). To use this data with convolutional networks we will have to transform it to three dimensions ( (C\times H\times W ) \), increasing first the amount of components with at least one fully connected layer and resizing the result. Later, we will add convolutional layers so that the result is a map of the dimensions of the spectrogram we are looking for. As the task we are trying to solve is symmetric (the encoder and the decoder must perform opposite tasks), we will opt for symmetric architectures for these two networks. If we have said that the encoder will start with a fully connected layer followed by convolutional layers, the decoder will start with convolutional layers and finally another fully connected one. In this way, the diagram above takes on the following structure:

Figure 3: Structure of a system with two subjects where number 1 is sent. By comparison with Shannon’s information theory, the central spectrogram shows the message. Only one part of the system is shown for the sake of simplicity.

Figure 3: Structure of a system with two subjects where number 1 is sent. By comparison with Shannon’s information theory, the central spectrogram shows the message. Only one part of the system is shown for the sake of simplicity.

To make a neural network system behave in a certain way, one must specify a quantity to minimize. This amount is called loss, and in many cases it is a function that depends on the network output and the original data3. Applied to our problem, we can immediately define a quantity that the system should minimize: we want B to interpret the same idea that A is trying to transmit. As there is only one correct number each time, the problem is multiclass (predict a number and only one of ten possible) and we will minimize the Cross-Entropy loss, defined as: \[ L_{CE} = - \sum_i^C t_i \log(s_i),\] where \( C \) are the possible classes and \( t_i \) and \( s_i \) represent the real and predicted labels, respectively(Gómez).

By minimizing the Cross-Entropy loss we get the two networks to agree on the number they are transmitting. It is important to point out that only by minimizing this function the networks would create an internal language at the output of the encoder, but this would very likely be random. As we want them to use R2-D2’s voice, we will have to add a function of loss more and we will do it… with style.

Speaking with style

As explained above, language must be created spontaneously and without human interaction, and for this purpose representation in the form of a spectrogram can help us. As it is evident, we cannot force the output of the encider to be equal (pixel by pixel) to a concrete spectrogram or to a group of these since we would be violating the second assumption of the problem (there would exist in that case strong human interaction). We will need then a less intrusive loss function, that does not look for differences by pixel but something more general. Fortunately, in 2015 a type of loss was introduced that is suitable for this use case: the style loss (Gatys et al.). Intuitively, this loss is calculated by passing the images through a pre-trained neural network (VGG) and comparing the intermediate representations of the target image and the generated image. The authors apply this idea to transfer the style of a picture to a photo, keeping the underlying idea of the original photo intact. For anyone interested, mathematically it looks like this with \( l \) intermediate representations:

\[ L_{style} = \sum_l w^lL_{style}^l, \] \[ L_{style}^l = \dfrac{1}{M^l} \sum_{ij} (G_{ij}^l(s) - G_{ij}^l(g))^2, \] where \( G(s) \) and \( G(g) \) refer to the Gram matrix of the style image and the generated image. For further information, I think this article can be interesting.

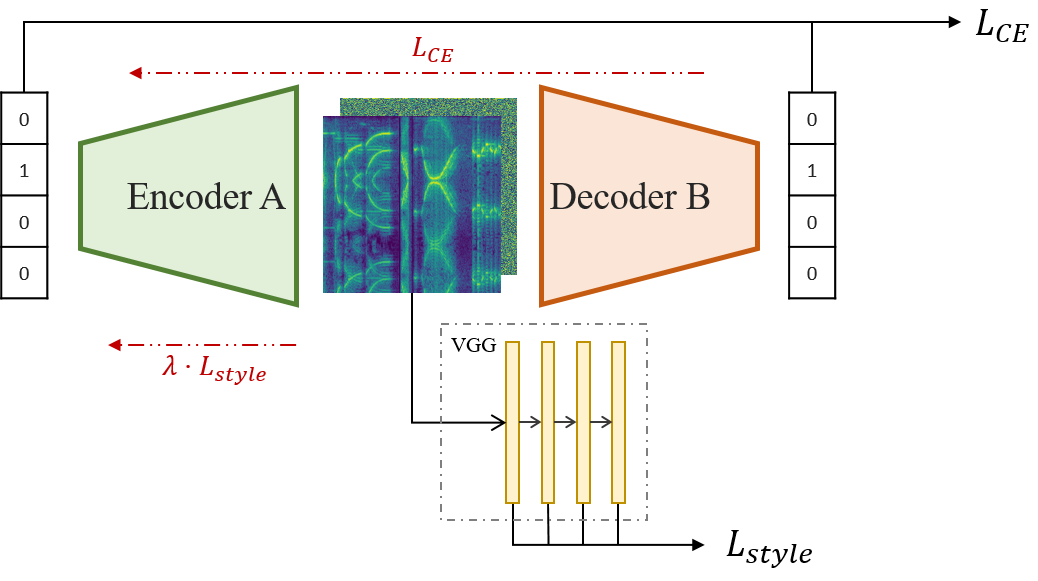

We can use the style loss to induce the output of the encoder to be similar to the reference spectrograms. This will presumably keep the sounds random but the result will remind us of the movie droid. However, this function cannot be applied to both encoder and decoder. Since only the encoder is involved in the language creation process, it is the only one that should receive feedback in this regard. However, the idea must flow through both networks, so the Cross-Entropy loss must spread throughout the system. Thus, the functions in each case result:

\[ L_{decoder} = L_{CE} = - \sum_i^C t_i \log(s_i),\] \[ L_{encoder} = L_{CE} + \lambda L_{style} = - \sum_i^C t_i \log(s_i) + \lambda \sum_l w^l \dfrac{1}{M^l} \sum_{ij} (G_{ij}^l(s) - G_{ij}^l(g))^2\]

And the whole system is:

Figure 4: Propagation and computation of the loss function throughout the system. Black: forward propagation. Red: backpropagation of the loss function.

Figure 4: Propagation and computation of the loss function throughout the system. Black: forward propagation. Red: backpropagation of the loss function.

One has to notice that the simplicity of the message we are transmitting can be a problem in order to train the encoder to generate an adequate representation, as it may cause the loss function to be unbalanced. Later on, we will make transmission harder with the addition of noise to the intermediate representation, thus making the input of the decoder different from the output of the encoder, perturbing the system and avoiding \(L_{decoder} = L_{CE} = 0 \) after a couple of training steps.

All that remains is choosing a training strategy. As described above, each subject is formed by two networks with different tasks and each communication faces different parts of each subject. Therefore, with \( N \) subjects we will have \( 2N \) networks and \( N^2 \) ways to face them (counting on the fact that we want a subject to be able to understand himself). To train all the subjects at the same time and avoid that some nets acquire more level than others we will have to follow a staggered strategy, alternating the training steps between all the combinations. Thus, both the time and the complexity of the training grow with \( \mathcal{O}(N^2) \). This strategy will also prevent the system from learning \( N^2 \) different languages, as all the networks will be learning in parallel.

Thus concludes the first part of this article on how to devise a system of neural networks from which a common language can emerge and how to make this language have the form we want. The second part will explore the results and other training strategies based on these. In addition, a noise source will be included to make the training more robust.

- Brown, Tom B., et al. Language Models Are Few-Shot Learners. May 2020, https://arxiv.org/abs/2005.14165.

- Shannon, C. E. “A Mathematical Theory of Communication.” Bell System Technical Journal, 1948, doi:10.1002/j.1538-7305.1948.tb01338.x.

- Neil, Carlson. “Physiology of Behavior.” IEEE Transactions on Information Theory, 2012.

- Bray, Adam, et al. Star Wars: Absolutely Everything You Need to Know. DK Children, 2015, p. 200.

- Krizhevsky, Alex, et al. “ImageNet Classification with Deep Convolutional Neural Networks.” Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, 2012, doi:10.1061/(ASCE)GT.1943-5606.0001284.

- He, Kaiming, et al. “Deep Residual Learning for Image Recognition.” Proceedings of the IEEE Computer Society Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, 2016, doi:10.1109/CVPR.2016.90.

- Stanford, Cs231n. CS231n Convolutional Neural Networks for Visual Recognition. https://cs231n.github.io/convolutional-networks/. Accessed December 21, 2020.

- Gómez, Raúl. Understanding Categorical Cross-Entropy Loss, Binary Cross-Entropy Loss, Softmax Loss, Logistic Loss, Focal Loss and All Those Confusing Names. May 2018, https://gombru.github.io/2018/05/23/cross_entropy_loss/.

- Gatys, Leon, et al. “A Neural Algorithm of Artistic Style.” Journal of Vision, 2015, doi:10.1167/16.12.326.

-

Actually the Wernicke area and the Broca area are connected by the arcuate fasciculus (Neil). ↩

-

Only the magnitude is shown in this spectrogram. To calculate it, the Fourier transform of the signal has to be computed, and that carries a phase that is not mentioned here but that is fundamental to make the inverse transform later. ↩

-

This applies for supervised models, where we know the value the model should predict for each input value. There are other types of algorithms (unsupervised, for example), in which this is not fulfilled and the loss function takes other forms. ↩